By Amy Howe

on Jun 17, 2021 at 11:51 am

This article was updated on June 17 at 5:16 p.m.

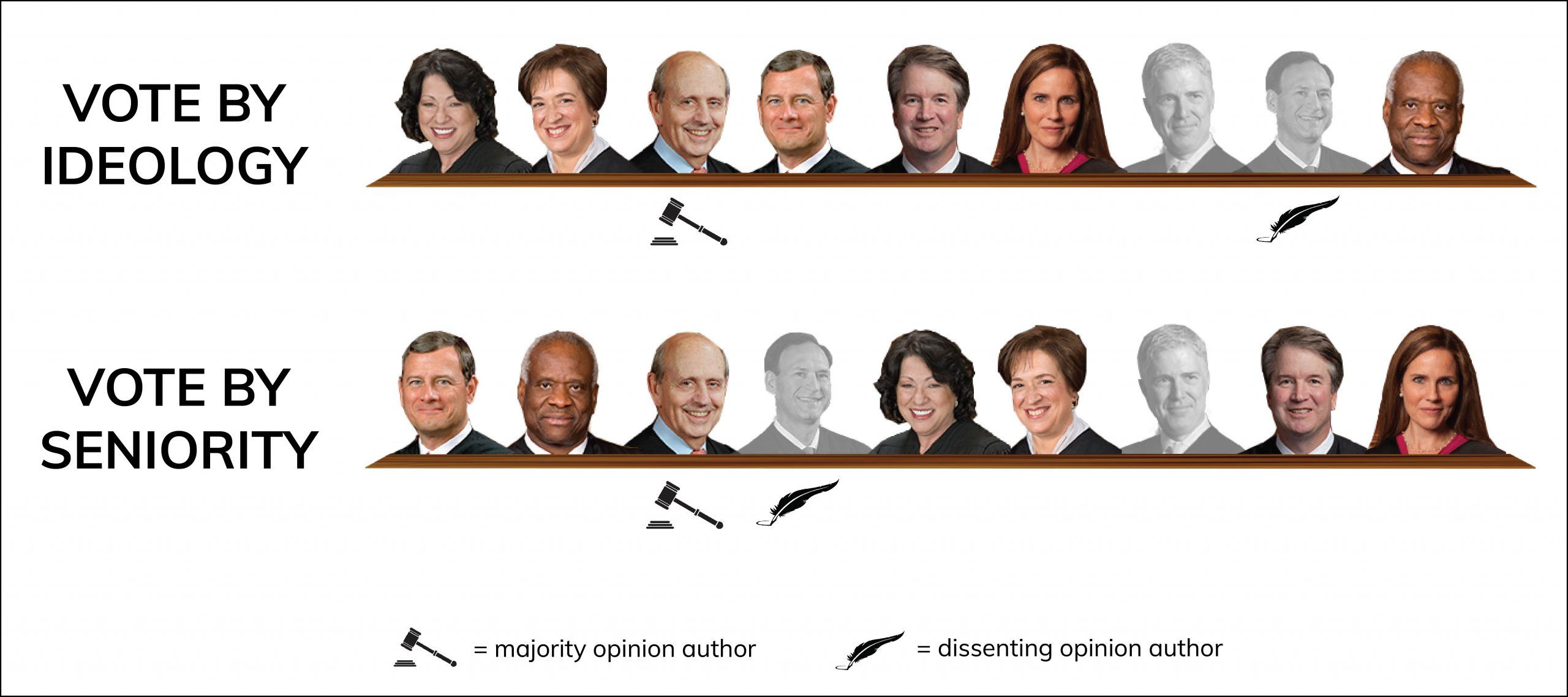

In a much-anticipated decision, the Supreme Court on Thursday rejected another effort to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, the health care reform law often regarded as the signature legislative achievement of former President Barack Obama. The justices did not reach the main issue in the case: whether the entirety of the ACA was rendered unconstitutional when Congress eliminated the penalty for failing to obtain health insurance. Instead, by a vote of 7-2, the justices ruled that neither the states nor the individuals challenging the law have a legal right to sue, known as standing.

Justice Stephen Breyer wrote the majority opinion. He was joined by the other two liberal justices, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, as well as four conservatives: Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett. Justice Samuel Alito wrote a dissent and was joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch.

The case, California v. Texas, was in many ways expected to be a sequel to the court’s 2012 ruling in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius. In that ruling, Roberts joined Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan and former Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in concluding that the provision of the ACA requiring individuals to have insurance – known as the individual mandate – was constitutional because it imposed a tax on individuals who did not comply. But five years later, Congress changed the tax penalty for failing to obtain health insurance, lowering it from $695 to $0.

The change in the penalty led to a new constitutional challenge. Texas and a group of other states with Republican leaders, as well as two men who did not want to buy health insurance, went to federal court, arguing that the mandate was now unconstitutional because it could no longer be justified as a tax. And if the mandate is no longer constitutional, they contended, all of the ACA’s other provisions – including Medicaid expansion and protections for people with pre-existing conditions – had to be struck down as well.

A federal district judge in Texas agreed with the challengers that the mandate is unconstitutional because the 2017 change to the penalty transformed the mandate into a “standalone command” to buy health insurance – something that Congress lacks the power to do. And without the mandate, the district court concluded, the entire ACA must fall.

On appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit agreed with the district court that, because the penalty for not obtaining health insurance is now zero, the current version of the mandate is unconstitutional. But the court of appeals said the case should go back to the district court for a closer look at whether the entire ACA is invalid as a result. The House of Representatives and a group of Democratic-controlled states, led by California, which had entered the case to defend the law, asked the Supreme Court to weigh in first. The justices agreed last year to do so.

Because the ACA is a federal law, the federal government would normally have defended it throughout the proceedings. But the federal government’s role was more complicated in this case. In the district court, the Trump administration did not defend the mandate; instead, it argued that the mandate was unconstitutional and should be invalidated (along with two other related provisions), but it urged the district court to leave the rest of the ACA in place. In the court of appeals and the Supreme Court, however, the Trump administration agreed with the challengers that the whole ACA should be invalidated.

In February, the newly elected Biden administration notified the justices that the federal government had changed its position in the case. In a two-page letter, Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler explained that the government now believed that the mandate is constitutional even after Congress reduced the penalty for failing to obtain insurance to zero. But if the justices disagree, Kneedler continued, they should invalidate only the mandate, and leave the rest of the ACA intact.

Unlike the tense 5-4 ruling issued on the last day of the term in the NFIB case, the court’s decision on Thursday was not particularly close: Six justices joined Breyer’s opinion holding that neither the states nor the individual plaintiffs have standing to challenge the mandate. The individual plaintiffs, Breyer explained, contended that they are harmed, and therefore have a right to sue, because they have to pay each month for health insurance to comply with the mandate. The problem with that argument, Breyer reasoned, is that although the ACA instructs them to obtain health insurance, the Internal Revenue Service can no longer impose a penalty on taxpayers who fail to obtain insurance – and there is no other government action connected to the harm that the individual plaintiffs claim to have suffered, a key requirement for standing.

Nor, Breyer continued, do Texas and the other states have standing to challenge the mandate. Although they alleged that they are injured because their residents, in an effort to comply with the mandate, enroll in state-sponsored programs like Medicaid, which costs the states money, Breyer emphasized that the states have not shown a link between the unenforceable mandate and the decision to enroll.

Breyer also rejected the states’ argument that the mandate imposes other additional costs directly on them – for example, the costs of providing information to beneficiaries and the IRS. Those requirements, Breyer explained, come from other parts of the ACA, rather than the mandate.

Because neither the individual plaintiffs nor the states have standing to challenge the mandate, Breyer concluded, the 5th Circuit’s holding that both sets of plaintiffs have standing is reversed, and the court sent the case back to the lower court with instructions to dismiss it.

In his dissent, Alito described the court’s ruling as the most recent chapter in “our epic Affordable Care Act trilogy,” a reference to the NFIB decision and the court’s 2015 decision in King v. Burwell, in which the justices – this time in a 6-3 vote – again rejected a challenge to a central component of the law. Alito lamented that Thursday’s ruling “follows the same pattern as installments one and two”: “[W]ith the Affordable Care Act facing a serious threat, the Court has pulled off an improbable rescue.”

In Alito’s view, the states have standing “for reasons that are straightforward and meritorious.” The majority’s holding to the contrary, he complained, “is based on a fundamental distortion of our standing jurisprudence.” As an initial matter, Alito wrote, the states are injured by the ACA: They “offered plenty of evidence that they incur substantial expenses in order to comply with obligations imposed by the ACA.” And if they were to prevail, Alito reasoned, they wouldn’t have to pay those expenses.

A key part of the dispute over standing, Alito noted, is whether the states’ injury can be traced to the federal government’s conduct. For Alito, the answer is yes. The states contended that the mandate is unconstitutional and that they wouldn’t otherwise have to pay the expenses that flow from provisions of the ACA that can’t be separated from the mandate.

Because the states, in his view, have standing to pursue their challenge, Alito turned next to the merits of their claims. As he did in 2012, Alito believed that the mandate is unconstitutional. But even if it was constitutional then, he continued, it no longer is in its current form. Moreover, Alito added, the provisions that impose costs on the states are “inextricably linked to the individual mandate” and therefore should not be enforced against the states.

In a concurring opinion, Thomas responded to Alito’s dissent. “Although this Court has erred twice before in cases involving the Affordable Care Act,” Thomas agreed with Alito, “it does not err today.” Here, Thomas stressed, the plaintiffs “have not identified any unlawful action that has injured them.” And Thomas pushed back against Alito’s argument that the states have standing based on “costly obligations imposed on them by other provisions of the ACA [that] cannot be severed from the mandate.” The states did not make this argument in the lower courts, Thomas noted, and the lower courts “did not address it in any detail.”